Assessing result-based interventions

Discover how evaluation can support the design of result-based interventions (RBIs), assess their progress during implementation and assess their overall effects and contribution to the corresponding objectives after their completion. Focusing on actual results achieved, RBIs offer the potential for a more precise evaluation of policy effectiveness.

Page contents

Basics

In a nutshell

Result-based interventions (RBI) for the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) are the ones that provide a payment – or at least a component of thereof – to beneficiaries that is directly linked to and dependent on the achievement of defined and verifiable results.

This definition depends on how results are defined. Results are measurable parameters directly linked to the objective the intervention aims to contribute (e.g. for biodiversity, the number of species present in a supported grassland). Still, they may also include measurements reflecting a reduction of pressures or threats to the environment (e.g. measuring the reduction of pesticide use instead of the concentration of active substances in water bodies). These results can be verified through on-site monitoring or predicted using robust scientific modelling approaches in cases where on-site monitoring is not feasible. In the case of modelling approaches, an independent auditor might be required to verify the results at an appropriate point in time to better qualify as RBIs.

The main characteristics of RBIs include the following:

- Beneficiaries (e.g. farmers or other land managers) must be allowed the flexibility to choose the most appropriate management to achieve the result.

- RBIs can provide a single payment level for achieving a result threshold or include differentiated payments that reflect different levels of the quantity and/or quality of the results achieved. In the case of modelling approaches, payment may be structured in a way that smaller payments, based on modelled results, are made during the implementation. In contrast, a balloon payment is made upon the verification of the actual results by an independent auditor.

- Result-based CAP interventions can be implemented by individual beneficiaries or a group of beneficiaries (e.g., collective farmers), depending on the type and level of objectives of the intervention and may include guidance on management practices that have a higher potential to deliver the desired results.

Interventions that link payments to a) the immediate outputs of actions (e.g. the presence of a hedgerow is the direct output of planting or maintaining a hedgerow) or b) merely the changes in farm practices and not their results should not be considered result-based.

Relation to the CAP

Biodiversity is the most common objective that RBIs contribute to. Effective biodiversity monitoring often requires a combination of indicators, including both biotic (e.g. species presence) and non-biotic (e.g. habitat structure) metrics.

Few RBIs deal with water and soil quality. They employ indicators mostly related to reducing pressures and threats to these natural resources to overcome challenges related to the time lag for measuring real impacts in terms of nitrogen balance, for example. Innovative approaches like catchment-level indicators may also be required.

Although only one example of an intervention related to animal welfare was identified in the report, there is considerable knowledge regarding indicators that can be used for this and antimicrobial use. If combined with dedicated livestock monitoring systems, they can set the basis for effective monitoring, reporting and verification processes.

One intervention identified in the CAP Strategic Plans related to carbon farming used the changes in the farm carbon balance as a result indicator. However, there are numerous approaches outside the CAP that operate under voluntary carbon markets. These are public, semi-public and private schemes that rely on modelling the potential of a pallet of practices to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or increase carbon sequestration to estimate results and calculate payments. In some cases, these modelled results are further verified by soil measurements in the field.

Although RBIs may have been developed to contribute primarily to a certain objective (e.g. biodiversity), they often deliver co-benefits that extend their contribution to additional objectives, e.g. water or soil quality. This means that RBIs can be designed to accommodate a whole farm approach that compensates the beneficiaries for the total environmental services they provide. However, the inherent complexity of designing interventions targeting multiple objectives and co-benefits requires careful planning for both beneficiaries and administrators. To alleviate this, scorecards may be helpful to link payments to results, enabling comprehensive and holistic assessments across environmental objectives.

The examples of RBIs included in the CAP Strategic Plans have not yet been evaluated. However, various evaluation studies have been conducted in different countries and agricultural contexts. These highlight common themes, methodologies and results, setting the agenda for future assessments and research. Several studies (see the ‘Learning from practice’ section for more details) have been conducted, where some evaluated actual policies or policy reforms, while others evaluated realistic scenarios built on simulations.

What to evaluate?

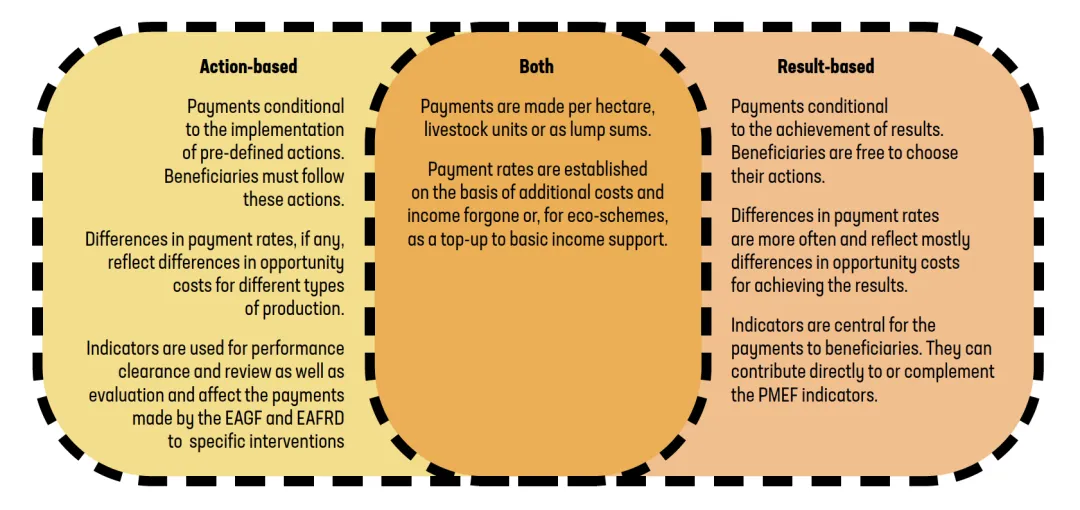

Action-based versus result-based interventions

The aim of the evaluation of RBIs does not differ from the aim of the assessment of any other interventions. However, evaluation should consider specificities arising from the differences between action and RBIs.

-

RBIs can transform evaluation activities because they challenge the conventional way we interpret and examine the evaluation criteria. In RBIs, the effectiveness of the intervention is directly linked to measurable environmental outcomes. Thus, effectiveness may be measured by the ‘kilogrammes of particulate phosphorous (PP)’ that is abated by implementing a measure of buffer strips (see Sidemo-Hom et al. 2018 for more details).

The evaluation process can be impacted by the differences between action-based and results-based interventions, such as:

- the payment for results and the sensitivity of the payments to the different levels of results achieved to incentivise better performance and more significant environmental benefits;

- the flexibility beneficiaries enjoy in determining the most appropriate practices to achieve the expected results; and

- the consequent requirement is for a robust system of measurable and identifiable indicators responsive to agricultural practice changes, as these are central for calculating the payments to beneficiaries and assessing the contribution of each beneficiary towards the objectives.

According to the European Commission’s Better Regulation Toolbox, the policy's objectives and targets for each beneficiary and the corresponding interventions should be expressed in physical units of environmental outcomes and compared against a baseline. For instance, evaluating gross effectiveness means that the baseline, the targets and the progress can be measured in physical units of the environmental outcome. In other words, to make full use of the potential of RBIs to demonstrate better the performance of the policy, the objectives, as well as any targets set at Member State or intervention level, must be aligned with how results are measured at the level of the beneficiaries.

The second significant difference between RBIs and action-based interventions stems from the reliance on achieving specific environmental or agricultural outcomes for payment. It leads to higher perceived uncertainty and risk at both ends of the contract, farmers and administrations. In RBIs, the non-payment risk is higher for the beneficiaries because payments are contingent on achieving and accurately measuring specific outcomes.

This risk can be a barrier to participation, creating uncertainty for the administration as regards the achievement of the targets set in the CAP Strategic Plan and the implication for performance clearance and review. From the evaluation point of view, perception of higher than usual risk may impact the uptake rates and farmers’ satisfaction and introduce bias concerning risk attitudes on top of a bias related to comprehension and familiarity with the RBIs. These will have severe implications for the scheme’s effectiveness and the methodological options open to the evaluator.

Measuring results

Indicators used to measure results are central to calculating the payments to beneficiaries. They must have specific characteristics that ensure they are reliable, practical and aligned with the intervention’s objectives. Evaluators must ensure that the indicators are:

- Measurable, quantifiable and verifiable cost-effectively and practically through field inspections, remote sensing or other appropriate methods within the constraints of the available resources.

- Sensitive and responsive to farmers’ specific actions as regards management practices and changes in management practices.

- Clear, simple and understandable by all stakeholders, including farmers, administration, policymakers and evaluators.

- Aligned with the environmental, climate and other policy objectives the RBI contributes to.

- Consistent and reliable in providing data across different contexts and over time, allowing for environmental, climatic and socioeconomic factors.

The role of evaluation

Evaluation can play a significant role in all stages of RBIs. In the design phase, it can be used to understand and find ways to mitigate beneficiaries’ and administrations’ perceived risks and make the interventions more appealing, also considering any potential unintended effects, such as, for example, attracting only beneficiaries with specific skills or farm characteristics that are better positioned to navigate the complexities of RBIs, thus compromising the fairness and equity of the intervention. Topics may include how the results are defined, what indicators and targets can be used, and what measures should be taken to mitigate risks for beneficiaries and administration while ensuring compliance with applicable rules.

During the implementation, evaluation can be used to assess rates of adoption and the effectiveness of strategies used to mitigate beneficiaries’ perceived risks. Its role is also critical for determining the results' attainability, timeliness, validity and coherence with other non-RBIs. Since beneficiaries of RBIs can choose the most appropriate management practices to achieve the results, evaluations during the implementation can examine the effectiveness and efficiency of the different approaches by constructing and analysing the different intervention logics.

After the implementation of RBIs, summative evaluations (i.e. evaluations carried out after the completion of the implementation of the RBIs) – which can be either stand-alone evaluations, assessing only these interventions or part of the ex-post evaluation of the CAP Strategic Plan – can provide insights on the demographics of the beneficiaries reached but also at the difference between the environmental outcome of an intervention and a hypothetical baseline of what would have been the outcome in the absence of this intervention (i.e. additionality) and permanence of results. The costs of the implementation and the efficiency of these interventions can also be assessed. These evaluations can also show how these interventions contribute to the corresponding objectives and how measured results can complement the PMEF indicators and better demonstrate the performance of the CAP.

Step-by-step

Ex-ante evaluation of RBIs

Step 1 – Conduct a SWOT analysis and/or needs assessment

The ex ante assessment ensures the relevance of the interventions by verifying that the proposed RBIs align with the needs identified in the CAP Strategic Plan through SWOT analysis and needs assessment.

Step 2 – Identify the needs which the RBI aims to address, along with the objectives it aims to contribute to

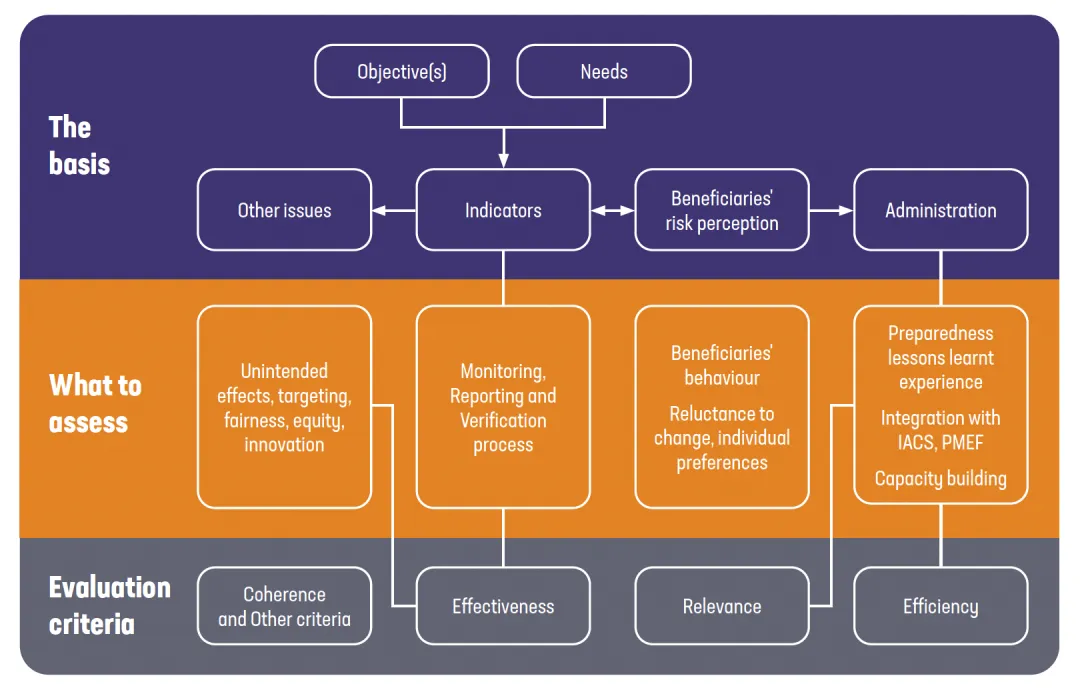

The basis of this assessment is determined by the identified needs the RBI aims to address and the objectives it contributes to. These shape the definition of expected results and the indicators used to measure them, which, in turn, influence beneficiaries’ risk perception and the challenges faced by the administration.

Evaluators should carefully assess the characteristics of indicators outlined in Section 2 of the thematic report and ensure alignment with the following criteria:

- Defined objectives

- Measurability

- Sensitivity to changes

- Feasibility

- Cost-effectiveness

- Stakeholder relevance

- Baseline establishment

- Applicability to local contexts

Failing to capture the above characteristics will result in diminished accuracy, monitoring and overall cost-effectiveness of observed interventions in the RBI evaluation.

Step 3 – Determine whether the results and indicator formulation meet the required criteria

Ex ante evaluators should assess whether the formulation of results and corresponding indicators meets the required characteristics, as described in the section 'Measuring results' above.

Step 4 – Develop a risk management plan for RBIs

A risk management plan ensures the proposed interventions achieve their intended targets while attracting beneficiary participation without generating adverse economic, social or environmental impacts.

Evaluators can follow the following risk management plan for the observed RBIs:

Identify risks

- Economic risks: assess potential issues such as insufficient payments, high upfront costs, unstable market conditions, and low cost-effectiveness.

- Social risks: identify risks of marginalising vulnerable households with limited access to resources, skills, or information.

- Environmental risks: consider unintended negative environmental impacts.

To address identified risks, stakeholder consultations should be conducted along with field assessments and baseline studies that gather insights on the abovementioned risks.

Analyse and assess the risks

- Probability and impact analysis: evaluate the likelihood and severity of each identified risk.

- Vulnerable group identification: ensure all affected groups are considered.

Qualitative and quantitative methods should be utilised to tackle the estimation and exposure to (the scale of) risks across different groups and participants.

Implement monitoring and adaptive management.

- Continuous monitoring: track economic, social and environmental indicators in real-time.

- Adaptive management: design a flexible framework to allow modification to the RBI based on available monitoring data

Scorecards, field assessments and participatory monitoring can be used to establish a feedback loop that ensures that interventions are responsive and data-driven.

Develop risk mitigation strategies.

- Economic mitigation: ensure RBIs have adequate payment structures, consider hybrid models, and provide financial support (e.g. grants, low-interest loans, etc.).

- Social mitigation: make participation criteria inclusive and flexible to accommodate diverse households.

- Environmental mitigation: use adaptive management approaches to monitor practices in real-time and select environmental indicators that avoid unintended consequences.

A mitigation plan for each risk should be created to ensure clear strategies for adaptation if risks materialise. Moreover, stakeholders should be involved when designing solutions.

Build resilience and contingency plans.

- Resilience building: ensure the RBI promotes practices that enhance environmental and socioeconomic factors.

- contingency planning: prepare for high-probability, high-impact risks (e.g. extreme weather) by developing alternative strategies for resource allocation and payment adjustments.

A clear outline of response measures to unexpected shocks or disruptions ensures participants are not unfairly penalised due to force majeure incidents.

Step 5 – Select the right indicators

Indicators for measuring results must be clear, easily identifiable, and measurable by beneficiaries and monitoring actors (i.e. Paying Agencies). They should align with environmental and climate objectives acceptable to land managers, be sensitive to changes in agricultural practices, and minimise influence from external factors to reduce risks for land managers.

Additionally, non-payment-linked indicators can provide a more comprehensive view of an RBI’s environmental impact, e.g. tracking invertebrate abundance and diversity to assess biodiversity. These indicators help mitigate the risk of external factors obscuring key results, enhance land managers' understanding of environmental objectives and identify potential risks or unintended consequences, such as favouring one species at the expense of another. Experience also highlights the challenges of linking farm management changes to environmental outcomes. Some impacts may not be immediately measurable, thus requiring long-term monitoring i.e. RBIs targeting water quality may be more effective at the catchment level, involving both agricultural and non-agricultural land managers, as farming is one contributing factor and not always the most significant.

For RBIs where the effects cannot be effectively manifested during the early years of implementation, a good practice is to develop an evolving monitoring system. This system may initially use pressure and threat indicators – i.e. those related to soil and water quality – to assess early-stage impacts and to gradually incorporate direct impact indicators over time to measure the intervention’s long-term effects.

The evaluation must assess how the indicators fit within the PMEF and how they connect with, contribute to, or complement PMEF impact indicators.

-

Conceptual framework of an ex ante evaluation of result-based interventions.

Suppose the observed RBI is designed to incorporate extensive areas or achieve considerable and crucial results. In that case, an ex ante evaluation may consider drawing a risk management strategy and hedging the RBI against low adoption rates and the consequent administrative risks of failing to produce results through this intervention. Annex IV of the report outlines the stages and contents of a risk management strategy for RBIs during the ex ante evaluation.

Evaluation of RBIs during implementation (ongoing evaluation)

Step 1 – Establish the basis for ongoing evaluation

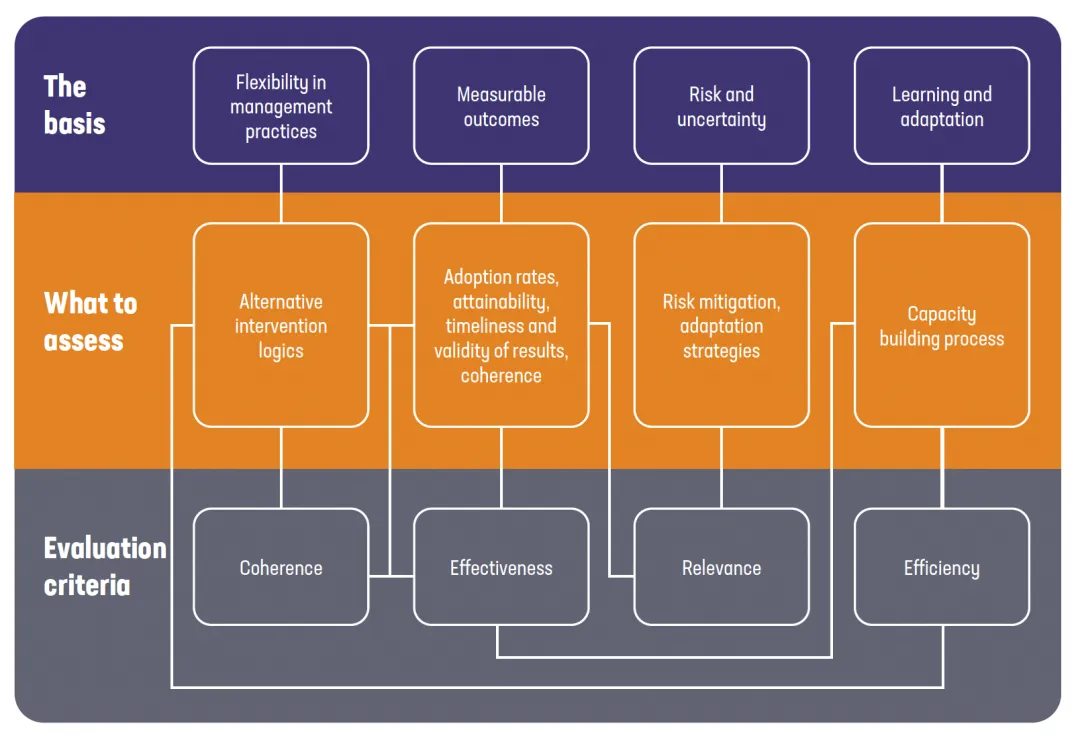

Ongoing evaluation ensures that RBIs remain effective by focusing on measurable environmental outcomes rather than just compliance with prescribed actions. Since payments are directly linked to results, sophisticated monitoring systems are required to verify actual impacts. Beneficiaries can choose their management practices, making evaluation more dynamic and context-sensitive. However, external factors like weather and pests add uncertainty, requiring a more adaptive approach than action-based schemes.

Step 2 – Implement frequent monitoring and risk mitigation

Regular evaluation is necessary to track progress, assess whether expected results are being achieved and identify external risks. Given the inherent uncertainties of RBIs, adaptive management strategies must be in place to ensure that factors beyond their control do not unfairly disadvantage participants.

Step 3 – Assess key issues during implementation

The evaluator must determine if adoption rates are satisfactory and whether expected results can be realistically attained within the intervention timeframe. The accuracy of monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) systems must also be ensured without creating unnecessary burdens for beneficiaries. Coherence with other interventions should also be assessed to identify any trade-offs or conflicts that may arise.

Step 4 – Evaluate alternative intervention logics

Since beneficiaries can choose their management practices, there is a possibility that different intervention logics will emerge, which will connect the management practices with the results achieved. These alternative intervention logics could be compared regarding their difficulty, costs, effectiveness and efficiency. Evaluators should also consider potential co-benefits and assess how well each intervention logic aligns with the different objectives it may contribute. These insights can help determine which intervention logic may be better transferable to other contexts.

Step 5 – Provide recommendations and adaptation strategies

Based on evaluation findings, adjustments may be needed to improve adoption and overall effectiveness. Recommendations should focus on refining delivery mechanisms, mitigating risks and enhancing participant support through targeted advice and capacity building.

Step 6 – Assess learning and adaptation processes

A key part of the ongoing evaluation is understanding how beneficiaries and administrators learn from the process. Evaluators should assess how continuous capacity-building contributes to improved implementation, better outcomes and increased adoption of RBIs over time.

-

Conceptual framework of an ongoing evaluation of result-based interventions.

Assessment after the completion of RBIs (summative evaluation)

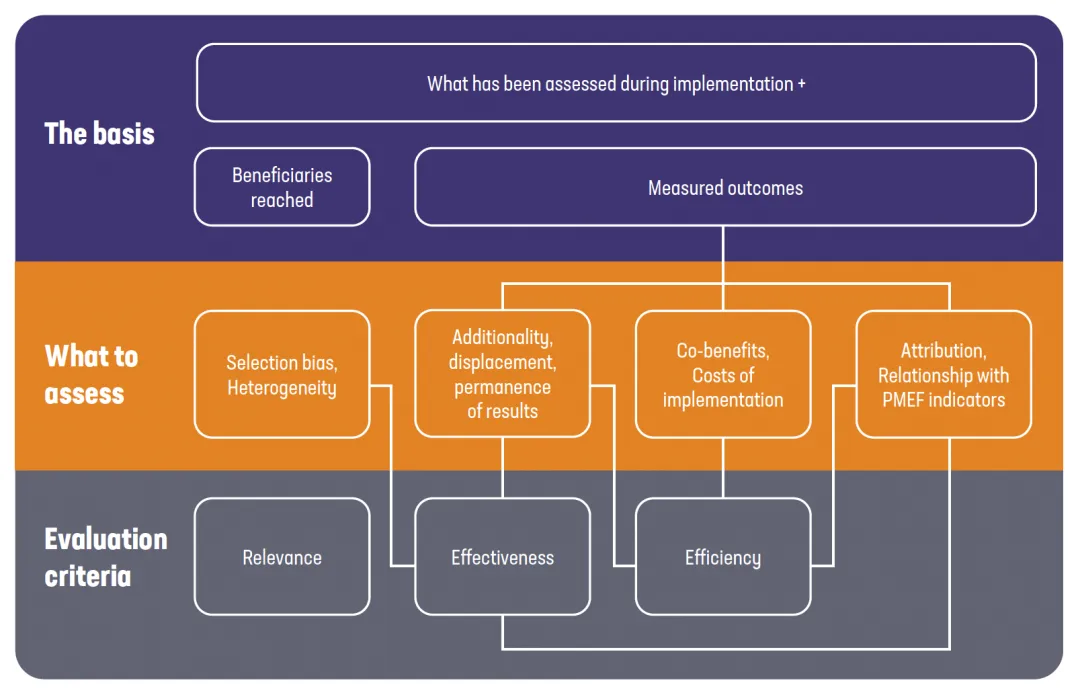

Step 1 – Establish the basis for summative evaluation

Summative evaluation takes place after the completion of an intervention to assess the overall quality of RBI implementation. It builds on ongoing assessments and final data on beneficiaries and results achieved. The key goal is to extract lessons learned and provide recommendations for future policy improvements, identifying successful approaches and areas needing refinement.

Step 2 – Assess adoption rates and participant diversity

Evaluators must examine the heterogeneity among potential adopters and assess how selection bias may have influenced uptake. The adoption process should be analysed regarding perceived risks, fairness, and inclusivity. Understanding participation levels provides insight into the intervention’s accessibility and effectiveness in reaching diverse farming communities.

Step 3 – Evaluate the effectiveness and impact of RBIs

The scale of environmental impact must be assessed by examining uptake rates and the extent to which the intervention achieved its intended results. This includes evaluating the barriers and motivators that influenced participation and the socioeconomic of the intervention. Insights from adoption studies and satisfaction surveys can help refine future interventions.

Step 4 – Determine additionality and net effects

A key focus of the summative evaluation is determining additionality and whether the results would have been achieved without CAP support. Establishing environmental baselines at the start of interventions helps quantify additional impact. Comparing participating farms with non-beneficiaries can further improve the accuracy of net effect assessments.

Step 5 – Analyse the integration with PMEF indicators

RBIs generate extensive data that can complement PMEF indicators, particularly in measuring environmental and climate impacts. By aligning RBI indicators with PMEF metrics, evaluators can better attribute observed changes to policy interventions and enhance future monitoring efforts.

Examples of the complementarities between RBI and PMEF indicators can be found for the following objectives below:

Biodiversity

| PMEF | O.14, O14 | R.31 | I.19, I.20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBIs | Total number or % change of ‘positive’ species; Total number or % of ‘negative species’; Number of nests or % change of the area of nesting habitats per bird species. |

Water quality

| PMEF | O.14, O14 | R.21, R.22, R.24 | I.15, 1.16, I.18 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBIs | % change in pesticides treatment frequency indicator; Change in the assessment of risk to the quality of natural water bodies. |

Soil quality

| PMEF | O.8, O14 | R.19 | I.13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBIs | Change in the extent of bare soil or erosion. |

Climate change mitigation

| PMEF | O.8, O14 | R.14 | I.10, I.11 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBIs | Reduced GHG emissions, sequestered carbon, and carbon balance improvement. |

Animal welfare

| PMEF | O.18 | R.44 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBIs | Absence of injuries: % of animals with intact tails. |

Step 6 – Provide recommendations for future policy design

Based on evaluation findings, recommendations should focus on improving intervention design, monitoring processes and capacity-building efforts. Addressing identified barriers, refining adoption strategies and strengthening evaluation methodologies will help enhance the effectiveness of future RBIs.

Summative evaluations of RBIs should assess the permanence of environmental outcomes and whether practices continue beyond financial incentives. Evaluators must capture co-benefits alongside primary results, using broader indicators and methodologies while considering potential adverse effects such as displacement and leakage. A comprehensive evaluation is justified for large-scale RBIs with significant agricultural impact, while smaller interventions should focus on flagging risks and benefits.

Co-benefits often align with other CAP Strategic Plan objectives, highlighting the need for coherence assessments. Spatial targeting should be evaluated for effectiveness, ensuring optimal resource allocation. Lastly, summative evaluations must review adaptive management and risk mitigation strategies, examining their effectiveness in addressing challenges and fostering long-term resilience.

-

Conceptual framework of summative evaluations of result-based interventions.

Main takeaway points

- RBIs link payments to measurable and verifiable results rather than just actions taken. The results should be directly related to the intervention’s objective (e.g., improving animal welfare, pesticide reduction, ecosystems, etc.).

- Biodiversity is the most common objective for RBIs. Carbon farming is of emerging importance to the CAP through farm carbon balance indicators – with external, private or semi-private voluntary carbon markets using modelled emissions reduction or sequestration estimates.

- The key differences between action-based and result-based interventions which affect the design and implementation of evaluations include i) sensitivity of payments to varying levels of results, ii) the flexibility of beneficiaries when it comes to choosing practices, and iii) the need for robust, identifiable indicators to assess effectiveness.

- Evaluation should align objectives, targets and results with measurable environmental outcomes. However, the administrations and beneficiaries may perceive RBIs as too risky. Effective risk management must be central to evaluations during the design and implementation of RBIs.

- RBI indicators must be measurable, cost-effective, verifiable (e.g. field inspections, remote sensing) and reliable across different contexts and timeframes while maintaining sensitivity to changes in farm practices and the absence of policy objectives.

Learning from practice

- Block, J.B., Hermann, D. and Mußhoff, O., (2024).

Agricultural soils in climate change mitigation: comparing action-based and results-based programmes for carbon sequestration, Climatic Change, 177. - Kreft, C., Huber, R., Schäfer, D. and Finger, R., (2024).

Quantifying the impact of farmers’ social networks on the effectiveness of climate change mitigation policies in agriculture, Journal of Agricultural Economics, 75(1), pp. 298-322. - Sidemo-Holm, W., Smith, H.G., and Brady, M.V. (2018).

Improving agricultural pollution abatement through result-based payment schemes, Land Use Policy, 77, pp. 209-219. - Späti, K., Huber, R., Logar, I. & Finger, R., (2022).

Incentivising the adoption of precision agricultural technologies in small-scale farming systems: A choice experiment approach, Journal of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, 1(3), pp. 236-253. - Šumrada, T., Vreš, B., Čelik, T., Šilc, U., Rac, I., Udovč, A. and Erjavec, E., (2021).

Are result-based schemes superior to the conservation of High Nature Value grasslands? Evidence from Slovenia, Land use policy, 111, p.105749. - Villanueva, A.J., Granado-Díaz, R. & Colombo, S., (2024).

Comparing practice- and results-based agri-environmental schemes controlled by remote sensing: An application to olive groves in Spain, Journal of Agricultural Economics, 75, pp. 524-545. - Wuepper, D., and Huber, R., (2022).

Comparing effectiveness and return on investment of action-and results-based agri-environmental payments in Switzerland, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 104(5), pp. 1585-1604.